One of the Bay Area’s pioneering radio stations, KLX made its first broadcast on July 25, 1922. To be fair, it wasn’t a new station; about a year earlier, radio pioneer Preston Allen had obtained a license with the call letters KZM.

Allen operated KZM from his Western Radio Institute at the Hotel Oakland. Programs consisted of phonograph concerts broadcast Tuesday and Friday evenings, as well as daily news reports from 7:15 to 7:30, with news material supplied by the Oakland Tribune.

The relationship with the Tribune deepened to the point that Allen convinced publisher Joseph Knowland that the Tribune should apply for its own license. Allen would run the station from the school, and the Tribune would finance it. Thus was born KLX.

At the time, all stations operating in the area shared the same frequency: 360 meters (around 830 kHz on the modern AM dial). This meant they had to share the airwaves, signing on and off on a pre-arranged schedule. KLX was able t0 expand its on-air hours in mid-January 1923.

Broadcast frequencies were quite fluid in the early years; by the spring of 1924, KLX was being heard on 509 meters or roughly 590 kHz. FCC records show the station at 880 on the dial (341 meters) by 1929, a position it held until the North American Regional Broadcasting Agreement of 1941 when the license was shifted to 910 kHz.

Radio has generated many memorable personalities, but KLX and the Tribune did something quite unusual: they made personalities out of their transmitters. The 50-watt transmitter inherited from KZM was dubbed “Little Jimmie”, and its 250-watt replacement got the name “Powerful Katrinka” (both were the names of popular comic strip characters of the day).

Two days before the first KLX broadcast, the Tribune offered considerable detail about the transmitters in a story headlined “‘Powerful Katrinka’ And ‘Little Jimmie’ To Stir Ether Waves”. The morning after the inaugural transmission, Little Jimmie was reported to be “fatigued” by his efforts.

KLX acquired a role as the official broadcasting station for the City of Oakland, which led to such programming as the daily recitation of the license plate numbers of any automobiles stolen in Oakland within the previous 24 hours.

KLX played a role in an early effort to promote radio broadcasting. In December 1922, the Southern Pacific Railroad outfitted the observation car on the Overland Limited passenger train with an antenna, radio receiver, and loudspeakers. A telegram to SP headquarters in San Francisco confirmed that passengers were enjoying KLX as far east as Omaha.

In late 1923, KLX moved into the newly-completed Tribune Tower in downtown Oakland, occupying the 20th floor, which it would call home for the next thirty years. The new facility included a studio with enough space for the live musical broadcasts that made up an increasing portion of the station’s programming. The new home included a 500-watt transmitter which the Tribune boasted could be “heard over the greater portion of the Western Hemisphere”.

The Tribune printed countless column inches about KLX in its early years, going beyond simple program listings to carry laudatory letters from listeners and lengthy question-and-answer columns that served to build interest in radio in general–and KLX in particular.

KLX was one of about two dozen radio stations nationwide to carry an address by President Calvin Coolidge on October 23, 1924. It was delivered at the inauguration of the new U.S. Chamber of Commerce headquarters and during its 45-minute duration, stations not carrying the speech went silent. Coolidge would again be heard on KLX on the occasion of his second Inaugural Address in March 2025 (and the Tribune dutifully printed a number of letters from appreciative listeners).

The Knowland family’s Republican Party political power was always an important part of the Oakland Tribune/KLX story. Owner Joseph Knowland had served in the California Legislature and in Congress before buying the newspaper in 1915. His son, William F. Knowland, represented California in the United States Senate from 1945 to 1959. William F. Knowland’s decision to run for Governor of California in 1958 led to a loss to Edmund G. “Pat” Brown.

The station developed a strong specialty in sports programming, starting with its broadcast of the “Big Game” on November 24, 1923–the first game ever played at the University of California’s new Memorial Stadium and the first time an entire football game was broadcast live from the sidelines. Over the years, KLX would carry Oakland Oaks baseball (including re-creations of away games) as well as Cal and Stanford sports.

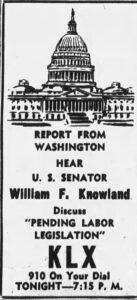

One of the most popular KLX programs during the ’20s was a variety show called the “Lake Merritt Ducks,” with Captain Bill Royal. Every Monday night at nine, the “quacking” of Royal and his comrades would announce that the weekly broadcast of the Ducks was on the air.

In the late 1940s, KLX carried broadcasts of the Oakland Bittners, an AAU basketball team that, in 1949, would win the national championship. A star player for the Bittners was Oakland native Don Barksdale, the first Black basketball All-American, the first Black American Olympic basketball player–and, in 1948 at KLX, the Bay Area’s first Black disc jockey.

From the mid-1940s to the mid-’50s, “Cactus Jack” (the air name of Clifton Johnsen) was a familiar voice on KLX, spinning country-western tunes and delivering down-home patter.

By 1956, KLX had outgrown its longtime home in the Tribune Tower. Plans were announced to move into the penthouse floor of the new Bermuda Building at 21st and Franklin Streets (that building would be demolished after sustaining heavy damage in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

The same chief engineer–Roswell “Ros” Smith–who had overseen the move from the Oakland Hotel to the Tribune Tower more than 30 years earlier managed the transition to the new site.

By then, KLX was operating at 5,000 watts, beaming its signal from a transmitter site at Richmond’s Point Isabel.

After all the words printed by the Oakland Tribune about KLX over the years, the story of the station’s sale published on March 24, 1959 was brief. KLX was being sold (the price was later revealed to be $750,000) to the Crowell-Collier Publishing Company, a venerable magazine publisher that had gotten into the radio business. Crowell-Collier owned KFWB in Los Angeles and KDWB in Minneapolis and would change the call letters of its Oakland station to KEWB.

ADDITIONAL EXHIBITS: