The History Of KRE

Berkeley, California

By John F. Schneider

The call letters KRE are full of radio history. They were first issued, in the beginning years of the twentieth century, to the side-wheeler steam ship “Bay State,” operated by the Eastern Steamship Corporation.[5] Early in the morning of September 23, 1916, the “Bay State” ran aground in heavy fog at the entrance to the harbor at Portland, Maine, where she had been bound from Boston.

All of the ship’s 150 passengers were rescued safely, but the ship was damaged beyond repair and decommissioned.[6] Because of naval superstition, the ship’s call letters were abandoned, not to be used again on any vessel. Thus, the call letters KRE became “grounded.”

In 1922, the Department of Commerce re-issued them to the Maxwell Electric Company, a small radio store on Adeline Street in Berkeley. Maxwell Hallauer owned the establishment, and assigned the job of operating the station to employee Thomas A. Fite.[8] A small transmitter was built and installed at the Claremont Resort Hotel in the Berkeley Hills, and a studio was assembled on the second floor. The station began broadcasting March 11, 1922.[7]

However, in those days before advertising, the cost of operating a radio station was probably too much for the little company. The station was sold to the Berkeley Daily Gazette newspaper in May of the same year, although the Maxwell Electric Company continued to operate the station.

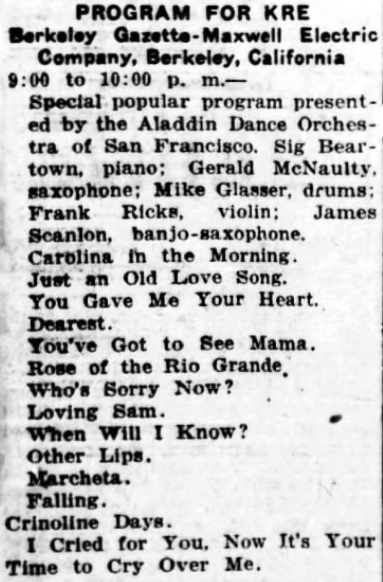

After it purchased the station, the newspaper’s pages suddenly came alive with news of radio. Regular radio columns helped publicize the fact that the little station was now broadcasting an hour every Sunday night. The initial program under the management of the Gazette was held May 23. The Gazette reported afterward:

Much interest was displayed Sunday in the dedicatory program of the Gazette radio broadcasting station at the Hotel Claremont. A program of songs sung by local vocalists was given, and during the concert several radio fans telephoned their congratulations, declaring the concert to be one of the best ever received locally. An excellent equipment made possible the clarity of tone, and the efficient management of operator Thomas Fite did the rest.[8]

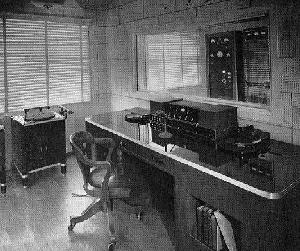

The added financial backing and influence of the Gazette brought several improvements to KRE during the ensuing months. The studio was rebuilt and hung with draperies to improve the acoustics, a piano was loaned to the station by Benjamin’s Music Store, and a phonograph by White’s. A 50-watt breadboard transmitter, nicknamed “Big Mike” (photo, right), was constructed by Maxwell Electric and installed by Fite. It began operating in August.[8]

The antenna used at the time was a vertical wire, suspended from two poles at the top and bottom of the hotel tower. From the bottom of the tower, directly above the porch, several counterpoise wires stretched out in all directions. The antenna was so situated that it faced towards the San Francisco Bay, so it would project its signal across Berkeley and Oakland and into San Francisco.[1]

Program content was also improved. Programs were expanded to two hours every Sunday. Fite did the announcing, and for program content the station enlisted Mrs. Wilda Wilson Church, head of the drama department of the Cora L. Williams Institute, an all-girl school in Berkeley.

Mrs. Church (at left in photo at left) prepared a weekly variety of music and poetry reading, drawing primarily upon students of her own college, students from Mill’s College in Oakland, and students of private music teachers in the area.[8]

She was to benefit greatly from this introduction to radio, and would leave KRE and the school in 1924 to become full-time dramatic director for the “KGO Players” at the General Electric radio station in Oakland. She would go on from there to NBC, and would become one of the nation’s better-known radio drama producers in the thirties. (Wilda Wilson Church was elected to the Bay Area Radio Hall of Fame in 2016.)

As listener response to KRE’s programs grew, programming time increased. In early 1923, Wednesday night was added to the schedule. Raymond Boyd and Frank Smith from Maxwell Electric were added to assist Fite in the operation of the station.

Program experiments were tried, usually with favorable results. On New Year’s Eve, 1922, the microphone was moved to the hotel’s main ballroom, and KRE broadcast the music and activities of the New Year’s Eve party there from ten o’clock until twelve thirty.

On April 8, 1923, KRE aired its first dramatic production. Members of the University of California’s Mask and Dagger Society gave a performance of “Dulcy” on the station, after three successful performances on the university’s Berkeley campus. The station’s usual musical repertoire consisted of classical music, but this was abandoned from time to time for programs of jazz. In July of 1923, the station initiated a series of educational programs with a discussion entitled “Stars and Planets” by Dr. R. B. Larkin.[8]

Prior to 1923, all radio stations had shared two frequencies. But in April of that year, because of the increasing popularity of the infant radio industry, the Department of Commerce assigned individual wavelengths to each station. KRE received an assignment to 278 meters (1079 kc); in the next few years, the station would also occupy 1170 and 1370 kc.

By late 1923, programming began to fall into a regular pattern. Music was usually provided by Vart Toujian’s “KRE Serenaders.” Wilda Wilson Church had left the station, and the Gazette now had to arrange the programs itself. The station became less of a new experience and more of a burden to the newspaper.

Maxwell Electric Company dropped out of the operation in December of that year, and the operation was taken over by L. H. Kettenger and G. B. Flood of the U.C. Battery and Electric Company.[8]

By the mid twenties, programming had become even more of a burden. Stations were now required to be on the air more than just a few hours weekly, and KRE was operating a weekly schedule of fifteen hours. Programs heard during this period included Horace Heidt’s Claremont Orchestra with regular dance programs. (Heidt was another person associated with KRE that later went on to national fame with the networks.)

Also during this period, the “KRE Players” offered several dramatic productions weekly. Thursday night was “educational night”; and every Wednesday afternoon, “Aunt Polly and Big Brother” presented their children’s program.[8]

Finally, the Gazette decided to rid themselves of the yoke around their necks. In January, 1927, they took the station off the air and put it up for sale.[8]

Meanwhile, the First Congregational Church in Berkeley was thinking about doing some broadcasting. They were investigating the possibility of leasing phone lines and airing weekly programs over KTAB in Oakland when they heard KRE was available. The church council minutes for January 19, 1927, show the following entry:

A motion was made that we authorize the trustees to do whatever may be necessary for the establishment of the broadcast station at the earliest possible date on our church property.[9]

By the end of January, KRE had been purchased for the modest sum of $6,000. The church shared in the purchase with the Pacific School of Religion in Berkeley, and the two were also to share in the use of the station.[8]

According to George Conklin, a retired professor at the Pacific School of Religion and member of the California Historical Radio Society:

PSR provided the money to make the initial payment of $1,000 for KRE and $995 to erect the antenna tower at the church. The money came from a lectureship trust established by E. T. Earl, the man who invented the refrigerated railroad car. He was a member of First Congregational Church in Oakland. The lectureship brought such people as Teddy Roosevelt to Berkeley to lecture, and no hall was large enough to hold all those who came. Therefore, the seminary trustees provided the initial funds in order to provide the lectures to a wider audience. [12]

KRE was off the air for several months while the equipment was moved and installed in the church building, at Dana and Durant Streets. A steel tower was erected, and an L-type wire antenna was strung from the tower to the church steeple. Underneath, a counterpoise was strung in an erratic manner to different parts of the building.[1]

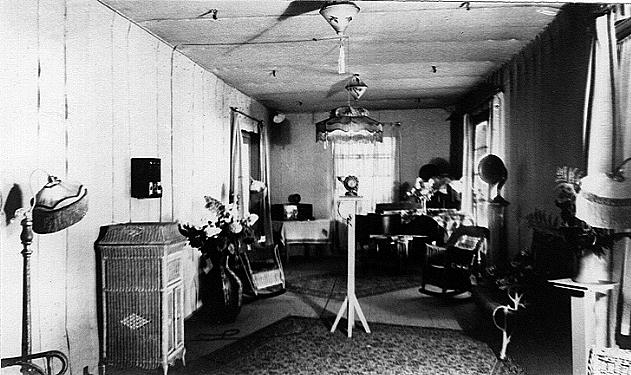

Inside the church, the studio was less than attractive. The transmitter and studio were combined into a single compact room behind the pipes of the church organ. A 100-watt breadboard transmitter was spread around the room, most of it mounted on top of a kitchen table. The Claremont Hotel was retained as a remote studio and tied to the church by phone lines.[1]

The station went back on the air in Spring, 1927, under the direction of Lawrence F. Moore. It shared its frequency with station KZM in Hayward, and the two stations alternated on the air several times daily.[9]

Programming was a mixture of religion and serious music. Where up to this time KRE’s music had been almost exclusively live, music programs were now strictly from phonograph records.

By 1929, the year of the Great Depression, the operation of the station left something to be desired. Funds were low, and the church admittedly knew very little about the operation of a radio station.

Finally, the church had decided it could no longer operate KRE alone. It entered into an agreement with KLS in Oakland, whereby that station would also operate KRE, with an option to purchase it at a later date.

However, after about five months, the church was not satisfied with the arrangement. KLS was not doing a credible job of operating the station, and KRE had received several off-frequency citations from the Federal Radio Commission.[3]

Meanwhile, the Chapel of the Chimes, a crematorium and mausoleum in Oakland, wanted to expand the audience for its program of organ music being broadcast from the chapel over KTAB in Oakland. Arthur Westlund, president of the chapel, arranged with KLS for the program to be broadcast simultaneously over KRE.

However, after only two broadcasts, KRE went off the air and remained off for three days because of equipment failure. Westlund talked to directors of the church and found them to be unhappy with the operation of the station by KLS. Westlund offered to operate the station himself, and the church promptly agreed. On January 4, 1930, the Chapel of the Chimes took over KRE, and Westlund became chairman of the church radio committee.[3]

Westlund took upon himself the task of placing KRE back into efficient operation. And it was a formidable one. According to the lease agreement with the church, the chapel would keep all the profits, as well as absorb any losses. KRE had attempted little on-air advertising up until this time, so Westlund began the station’s first full-time advertising campaign.

At first, he discovered he had a bad reputation to combat. According to Don Hambly, a KRE employee for many years, “the joke was that the manager would throw his hat into a store, and if it didn’t come flying back out, he would go in and try to give a sales pitch. It had that bad of a reputation!”

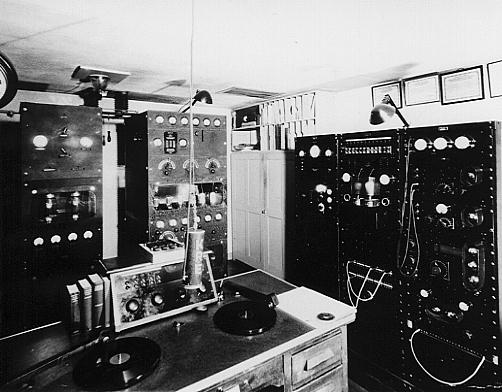

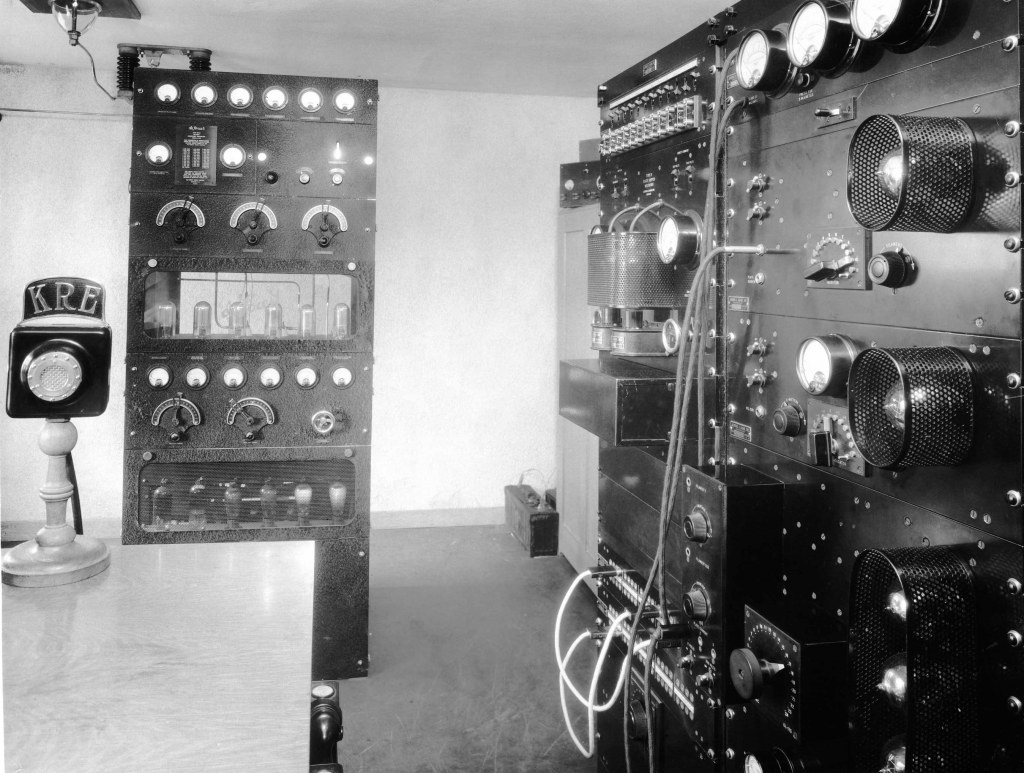

Hambly also described KRE’s transmitting equipment: “It had a breadboard transmitter scattered all over the room. To see if you were on frequency, you’d listen to the thousand-cycle beat oscillator over in the corner. If you wanted to tune the transmitter, you’d take a pool cue and hit the trimmer condenser with it, because your body capacity would put the transmitter out of tune if you got too close. It was a miserable mess.”[1]

Westlund’s Chief Engineer Ad Bideman replaced the transmitter with a 100-watt DeForest factory-built transmitter.

Programming was geared toward the people of Berkeley. For example, KRE became the official station of the “Daily Californian,” the University of California’s daily newspaper. This usually amounted to student Henry Schacht coming to the station every morning and reading the newspaper on the air for fifteen minutes.[1]

In 1931, additional studios were constructed at the Capwell Central Market in downtown Oakland. This was a supermarket owned by Capwell’s Department Store, and located across the street from the store. KRE’s studios and offices were on the mezzanine floor, on a balcony overlooking Telegraph Avenue.

The station broadcast from here during the daytime, and from the church and rebuilt Claremont Hotel studios at night. One of the programs emanating from the Capwell studios during this period was live country music by the Smokey Oaks Hillbilly Cowboys.[1,4]

Not too long afterward, the church received a petition from its neighborhood residents, complaining that the studio monitor speaker could be heard all over the neighborhood at night, through the station’s open window. The church asked Westlund to move the studios out of the church.

Because they could not use their Capwell’s studios at night, this necessitated a move to a full-time location. In the winter of 1933, the studios were moved to the Glenn-Connolly Building on Shattuck Avenue in Berkeley. The transmitter remained at the church.[1]

The year 1934 brought the Communications Act, and with it the Federal Communications Commission. Things changed rapidly after that, usually to the little station’s benefit. KZM had left the air in 1930, but KRE had been given only an additional three hours of air time by the old Federal Radio Commission.

In 1934, Westlund applied to the FCC for full-time operation. It was granted, and KRE became the first 24-hour station in Northern California. Jack Roseberg, a Berkeley college student, was recruited for the first all-night position.[1,3]

In 1935, the station was authorized to increase its power to 250 watts during the daytime, and the station’s engineers constructed a home-brew linear amplifier. The station continued to operate at 100 watts nights until the winter of 1939, when it was authorized for 250 watts full time.[1]

A 1935 ruling by the FCC expressly prohibited the operation of a radio station under a lease agreement such as the one between the Chapel of the Chimes and the church. Thus, an application was made to the FCC for the sale of KRE to Central California Broadcasters, a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Chapel of the Chimes. The sale was approved in December, 1936.[9]

One of the terms of the sale agreement stipulated by the Congregational Church stated that certain religious programs would be maintained by the station. These continued to be aired for a few years, until the FCC also declared this to be illegal, ruling that all program material must be in control of the management.[1]

Because the transmitter was still located at the church, a new transmitter site needed to be found. Westlund decided that the best location from a technical standpoint would be the bay shore. He asked Don Hambly to conduct an investigation and find out what Berkeley waterfront property was privately owned.

He discovered that the only piece of private property was at the southeastern edge of the city, and was entirely under water. As Hambly recalls, the property was owned by “two little old ladies. They evidently had to do quite a bit of dickering to get the property from them”[1]

Thus, KRE acquired the site known as 601 Ashby Avenue. The land had originally been tideland, and had been landlocked by the land fill from the construction of the Eastshore Freeway. The land had to be filled, and management filled only enough land to hold a building, tower and a small parking area. This was located in the middle of the water, and a narrow road was filled in to connect the building to the shore.[1]

The transmitter building was completed in June 1937. It contained the 250-watt transmitter moved from the church, plus audio equipment, a small control room and a workshop area. A 180-foot self-supporting tower was constructed, and the station’s call letters were mounted on its side in large illuminated letters.

Broadcasting magazine at the time commented, “six miles of ground wire were laid in the salt water near the tower to increase its efficiency.” The results were promising: calls from listeners indicated that KRE’s coverage had nearly doubled.[1,4]

Within the following year, the owners began constructing studio and office facilities at the site, turning the existing transmitter building into a state-of-the-art “art deco” facility. Hambly recalled that the sound of pile drivers crept onto the air quite frequently during this period. Finally, the entire operation was consolidated under one streamlined roof in November, 1938.[1]

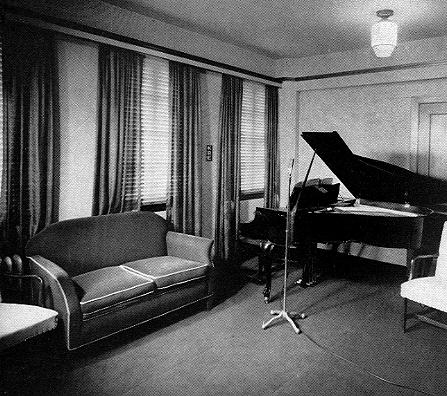

The building was one of the very few in the area constructed specially for broadcasting at that time. It included a control room and large studio, and an elevated announce booth that looked over the studio from a large bay window. No expense had been spared in soundproofing the studio. Westlund was a member of the radio committee for the 1939 World’s Fair on Treasure Island, and was in charge of constructing radio studios at the fair grounds.

He had hired some of the nation’s top engineers to design the studio, and managed to railroad them into designing KRE’s studio as well, at no extra cost. It was built exactly to their specifications. There was actually a room within a room – a floating studio. The inner walls of the studio were insulated from the outer walls by a three inch layer of insulating material. A three-inch thick, lead-lined door was the only access to the room. It was, at the time, considered a dream studio.[3]

However, even a dream studio isn’t always perfect, as Herb Caen pointed out in the San Francisco Chronicle in early 1941. The station was located directly adjacent to the Southern Pacific railroad tracks, and the sound of a roaring freight train would rumble through the studios seven times daily.

It was Don Hambly who finally conceived of a solution. The railroad was contacted and an advertising agreement was signed. Technicians installed a microphone on the roof of the building. Every time a train rumbled past the studios, the engineer would blow his whistle, and the announcer would fade out the record and ad lib a Southern Pacific commercial![10]

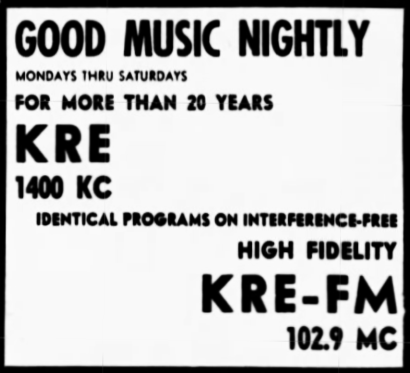

KRE’s frequency up until this time had been 1370 kc. In 1941, the FCC ordered a widespread re-allocation of frequencies, and KRE moved to its present location of 1400 kc.[4] The vacated 1370 kc. dial position was taken over in June 1947 by a new local station, KEEN in San Jose.

KRE’s programming during these years had evolved considerably. Although still mainly a music station, the programming was divided into blocks of different kinds of music.

The evenings featured mostly classical music. The afternoons were devoted to a program called “Open House,” hosted by Bert Solitaire, which was an important part of KRE for 25 years. This was a jazz request program, emphasizing big band jazz, especially the “hot clarinet” sound exemplified by Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw.

The organ in the Chapel of the Chimes was featured several times daily, for fifteen or thirty minute intervals. And, Italian and Portuguese programs were aired from two to three hours daily. Weekends were almost entirely devoted to religious and foreign language programs.[2]

There was very little news on the air during this period. The format was almost entirely music of one form or another, with the announcer ad libbing informally between records.[2]

KRE’s music format was a success, and the station rode the crest of popularity through the forties. After the war, Les Avery joined the announcing staff, and his evening program of classics, “Music of the Masters,” developed a tremendous following through the late forties and fifties.[2]

KRE was one of the first stations in the Bay Area to obtain an FM license. It constructed a transmitter site atop Round Hill Mountain in the Berkeley Hills, and KRE-FM went on the air Valentine’s Day 1949, simulcasting its AM programming on 102.9 mc. The FCC did not yet allow remote control of transmitting equipment, however, so an engineer had to be stationed at the transmitter site at all times.[1,4]

Public response to FM was disappointing, despite the number of stations on the air, and KRE soon found its FM station to be just an added expense, especially the cost of maintaining an engineer at the transmitter. Within a year, the transmitter had been moved to the AM site, and the land and tower were sold to the telephone company. Shortly thereafter, the FCC approved remote transmitter operation, but KRE-FM had already forfeited its prime transmitter location.[1]

In 1950, a second story was added to the studio building, adding additional needed office space.

Stereo became the latest audio craze in 1957, and KRE equipped for stereo broadcasting. It was one of the first stations in the Bay Area to broadcast in stereo, transmitting one channel on AM and the other channel on FM. This continued until 1959, when FM multiplexing was allowed.[4]

Disaster struck KRE April 17, 1957. A sudden windstorm descended upon the Bay Area, and did considerable damage. KRE operator Jack Dunn walked out the back door in time to see the station’s tower falling toward him. Luckily, the wind shifted and the tower twisted around and fell in the other direction. It broke off twenty feet above the base and stuck into the mud like a toothpick. The wind had apparently picked up the tower by the huge call letters mounted on its side.[1,11]

The station was off the air for several days until a temporary long wire antenna could be strung from the building to a nearby telephone pole. The station operated from this antenna for six months until a new tower was installed. The coverage was pitiful, and the station could not be heard with an adequate signal in downtown Oakland.[1]

In December, 1961, KRE’s daytime power was increased to its present 1,000 watts.[4]

Up to this time, the station had been under the continuous management of Art Westlund and the Chapel of the Chimes. However, Westlund decided it was becoming too formidable a task to try and manage both the chapel and KRE. And so, on March 15, 1963, the station was sold to the Wright Broadcasting Company, owners of the successful New York area station, WPAT, Patterson, N.J. Howard Haman became the new manager.

KRE thus became KPAT on April 29, 1963, at noon. The format was a duplicate of WPAT — continuous good music. Programs were divided into six program blocks, titled simple “KPAT Music One through Six.” Each music block was introduced by the ticking of the KPAT metronome.[4]

KPAT-FM raised its power from one thousand watts to fifty kilowatts in December, 1963, and broadcast multiplex stereo for the first time in June, 1966.

To increase its AM coverage, a taller tower was needed. So, in February, 1965, a 449-foot guyed tower was completed. In 1968, San Francisco’s KFRC moved its transmitter to the Ashby Avenue site, and the two stations began transmitting from the same tower.[4]

KPAT experimented extensively with its format in the ensuing years, but was not able to gain a significant foothold in the competitive San Francisco radio market. Finally, in 1970, KPAT was sold to Horizon Communications of California, Inc. Dale Moudy, manager of KNBR in San Francisco, became the new station manager, later replaced by Ollie Hayden. The station’s new programming was called “Radio Eastbay,” and in many aspects it recreated the successful Eastbay-oriented KRE programming of decades before.

On June 11, 1972, KRE commemorated its fiftieth anniversary with a huge celebration. In an unusual event, the FCC gave permission to KPAT to revert to its previous three-letter call sign. So “Radio Eastbay” again became KRE, alive and well and living in Berkeley!

POST SCRIPT: This article was written by John Schneider in 1972, to commemorate KRE’s fiftieth anniversary. It was originally published in the November 1972 issue of Performing Arts magazine. KRE has had several call letter changes since, becoming KBLX (August 1986-April 1989), KBFN (April 1989-August 1990), switching back to KBLX (August 1990-May 1994) and finally KVTO (May 1994-Present). The classic KRE studio and transmitter facility at Berkeley Aquatic Park fell into disrepair, and was turned over to the California Historical Radio Society (CHRS) which restored the building to its earlier luster. Subsequently, CHRS purchased its own building in Alameda; the old KRE building remains as the transmitter site for both the 1400 AM and 610 AM signals in the Bay Area.

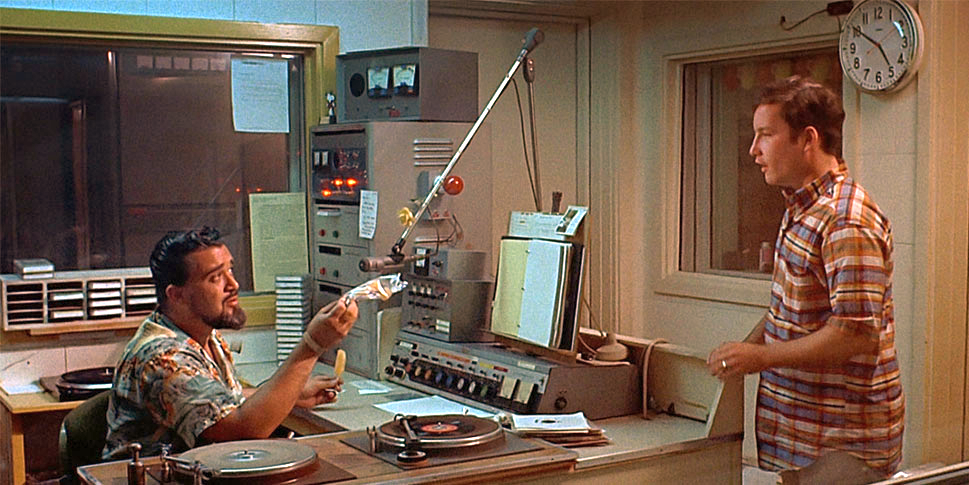

SIDEBAR: On August 3, 1972, a young filmmaker named George Lucas brought his crew to KRE in Berkeley to film a pivotal scene for his quasi-biographical movie, “American Graffiti.” The scenes, featuring Richard Dreyfuss (as “Curt”) and the legendary Wolfman Jack, were filmed at KRE’s front door and inside the station’s main studio. Some three decades later, the California Historical Radio Society recreated the same studio in the “American Graffiti” configuration – or close to it – which became a centerpiece of the organization’s “Radio Day By The Bay” open house events. For more on the filming of “American Graffiti” at KRE, please click here.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Interview between Don Hambly and author, Nov. 17, 1970. [2] Interview between Les Avery and author, Sept. 24, 1970. [3] Interview between Art Westlund and author, March 23, 1971. [4] “KRE/KPAT History,” a term paper by Patrick J. Hilliard, written Dec. 9, 1966, for the College of San Mateo, California. [5] “U. S. Government Callbook,” July, 1916. [6] “New York Times,” Sept. 24, 1916. [7] “San Francisco Examiner,” March 26, 1922.“Radio Service Bulletin,” Bureau of Navigation, Department of Commerce, May 1, 1922. (Listed in “The History of Radio to 1926,” by Gleason L. Archer; 1938, New York).

[8] “Berkeley Daily Gazette” radio column; May 20, 1922 through Jan. 12, 1927. [9] Congregational Church Board of Trustees minutes. Supplied by Eugene Frickstadt, clerk of the First Congregational Church. Minutes for the meetings of Jan. 19, 1927; Feb. 1, 1927; May 8, 1927; July 10, 1934; June 11, 1935; Aug. 13, 1935; Dec. 8, 1936. [10] Herb Caen, “San Francisco Chronicle,” January 14, 1941. [11} “San Francisco Chronicle,” April 17, 1957. [12] Letter to author by George Conklin, May 4, 2004.Copyright © 1997 John F. Schneider. All rights reserved.

For better views of the photographs, see the Photo Archives section of this website.

[Go to Index of Articles] [Go to Photo Archives] [Return to Home Page]

All articles copyright © 1997-2024 by John F. Schneider. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with the generous permission of the author.

My father, Bill Dyer, worked as a radio announcer at KRE in the 50’s. His program was all about jazz and big bands. His open lines were “Sit back, relax, and listen”. The DVD I have of that time is labeled “Sunday Session, Saturday Edition”.

So, Shari … how can the museum obtain a copy of that DVD? We’d love to include it in our archive.

DJ

Don Hambly was my great uncle, brother to my mother’s mother. He was not merely an engineer at KSFO, he was also an announcer well known in the Bay Area during the period when the San Francisco Giants were playing at the Cow Palace. One of his two sons, Scott, is a bluegrass mandolin player whose band was occasionally brought in to KRE to fill air time.

My husband, Rod, and I moved into Don and Flossie Hambly’s Berkeley apartment house with our baby daughter, Melissa in 1972. While living in that 3rd floor flat on Benvenue, our son Simon was born in 1973, and Elizabeth in 1974. It was spacious, light-filled and airy, and we loved living there.

Don and his wife Flossie were made to be landlords! They were interested in the tenants living in their 5 apartments and though all the other tenants were singles, we never felt peculiar in the group. The Hambly’s home was directly behind the Victorian apartment building in which we lived. They had a lovely garden but the bamboo was the bane of Don’s existence, always encroaching beyond it’s boundaries!

At Christmas, we all were invited to their home for a warm evening of great food, holiday beverages, amazing stories, and fondest friendship. In fact, the 2 tenants living on the second floor with whom we shared the staircase, Joan Wolff, who became a San Francisco attorney, and Frank Hubbard, who became a university professor, became our child’s Godparents. In season, the capable few would bring back their abalone catch for the day for the rest of us to pound into submission outside on the patio between the two structures. With white wine to revive the divers and to maintain the strength of the pounders, the evening got underway.

Don and Flossie always were invited to join us in the feast that accompanied the abalone. When we had to purchase a home in 1976, it was very, very hard to leave the place made magical by Don and Flossie. How extraordinarily fortunate we were to have lived there

My father, Nereo Francesconi, broadcasted in Italian from the late 30’s to the 1950’s. At 6 o’clock in the evening, every one in North Beach was tuned in! I spent some of my early childhood being dragged down to the station. Great memories with everyone there, especially with Paolo Albaquerqe (spelling?), the Portuguese broadcaster who followed my dad.