The History of KQW and KCBS

San Jose/San Francisco

By John F. Schneider

THE CHARLES HERROLD STORY

A great milestone in the history of broadcasting occurred in San Jose on January 1, 1909. That date marked the opening of an obscure engineering and wireless school. Its proprietor, Dr. Charles David Herrold, would be recognized by many, decades after his death, to have been the “father of broadcasting.”

Herrold was born November 16, 1875, in the Mississippi River town of Fulton, Illinois. Herrold’s father, Captain William Morris Herrold, was an inventor himself, and held patents on several agricultural devices. When young Charles was seven, Captain Herrold moved his family to Iowa. It was there, in the tiny community of Sloan, that Charles first began his education. He immediately showed an unusual scientific interest.

The only science books in the entire village were two volumes of Zell’s Encyclopedia, and Herrold read them from cover to cover several times. He quickly mastered all of his science and mathematical lessons, and, within a year of entering school, had built a perfectly-working telegraph line, including all of the instruments and batteries.

Enchanted with a visit they made to California, the family moved there permanently in 1888, and settled in San Jose. Once sufficient educational facilities were available to him, Herrold’s education improved rapidly. He entered high school in 1891, and again quickly excelled. He constructed a telescope and a driving clock, and used it to take photographs of the sun using a high-speed focal plane shutter of his own construction.

As a result of his experiments with this equipment, he fabricated a theory that sunspot disturbances were directly connected in some way with electromagnetic phenomena, or radio. This, of course, has since become a basic principle of radio theory.

Herrold graduated from high school after three years. It was then he first heard of Marconi’s experiments with wireless across the English Channel. This excited him greatly, and he read all the books he could find about the experiments of Hertz, Maxwell and others who had experimented in the areas of oscillating currents and electromagnetic waves. He experimented with wireless himself, and succeeded in transmitting a message sixty feet.

He entered Stanford University and began majoring in Astronomy, but later changed his major to Physics. One of his classmates at Stanford was later to become involved in radio licensing with the Federal Government, and would ultimately become President: Herbert Hoover.

Aside from a year’s leave of absence because of poor health, Herrold spent four years at Stanford, and then went to work for an electrical firm in San Francisco. While there, he developed a deep sea diving illuminator and several mechanisms for the pipe organ. He continued his work there until 1906, when the San Francisco earthquake disrupted his work.

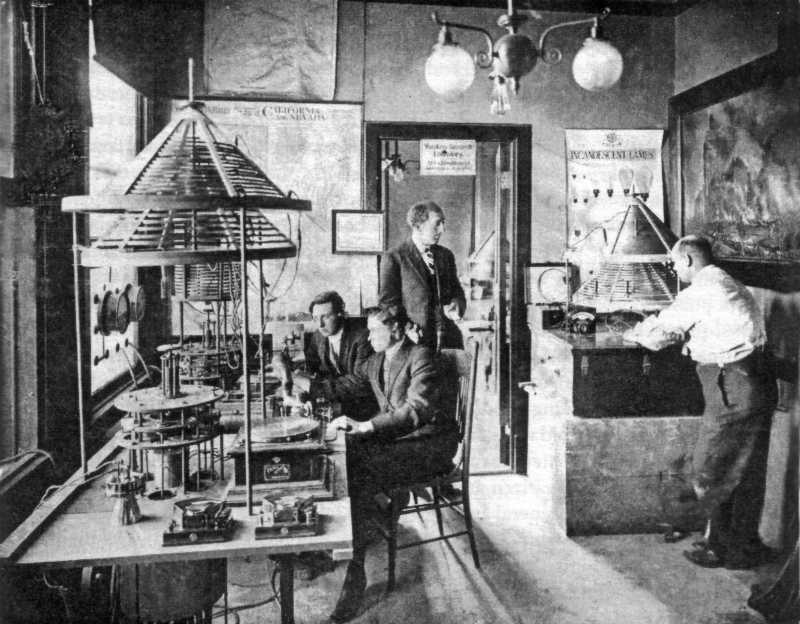

After the earthquake, he moved to Stockton, where he taught engineering at Heald’s College, and shortly after became head of the Technical Department. He and his students constructed a high-speed turbine and generator, and laid foundations in such areas as underwater wireless, the firing of explosive mines by radio, and radio telephony. He left Heald’s College and returned to San Jose in 1909, where he opened the Herrold College of Engineering and Wireless.

Herrold’s school was located in the Garden City Bank Building, later known as the American Trust Building, at First and West San Fernando Streets. A school specializing in wireless needed an antenna, and the Herrold antenna attracted the attention of most passers-by. It was called a “carpet aerial,” and it stretched like an umbrella over the bank building and to three smaller buildings alongside it. Altogether, the antenna was constructed from over 11,500 feet of bronze wire!

One of Herrold’s first and most active students was Ray Newby. He was interviewed in Stockton in 1959 by Professor Gordon Greb of San Jose State College, whose article about Herrold appeared in the “Journal of Broadcasting” in 1959. Newby was only sixteen when he and Herrold first transmitted voice from the school in 1909. He related the incident to Professor Greb:

I think what started the whole thing — so far as putting the voice out over this large antenna — was when I brought in a little one-inch spark coil and he had a microphone, and we connected the thing into a storage battery and talked into this microphone and rattled out some voice. And right away we began to hear some telephone calls that they had heard us.

The little fifteen-watt spark transmitter they had constructed was heard twenty miles away. This was the first of many transmissions heard from the school — transmissions that would continue for many years.

Soon after Herrold’s first voice transmission, experimenting began on a regular basis from the little spark transmitter. Newby related:

It got to be a habit with everybody. They would even call us up and want to know when we were going to test some more. And it was not long until we got into a pre-arranged schedule so that we would have listeners that could report to us … it was almost a religion with Professor Herrold to have his equipment ready and even only for a half hour on every Wednesday night at 9:00.

The only radio communication that amateur radio operators of the period had ever heard was Morse code. So, it was quite a thrill for them to hear voices coming out of headphones that usually produced only dots and dashes. Newby said, “The voice was a shock to almost anyone who heard it for the first time.”

Once Herrold realized he had an audience of eager radio experimenters, he began to entertain them. He would discuss news items and read clippings from the newspaper, or play records from his phonograph. This got to be a more and more important part of the school’s operations, and regular programs were heard from the station as early as 1910.

Herrold’s wife Sybil later got into the act. Using many techniques of the modern disk jockey, she regularly aired what she called her “Little Ham Program.” She later told Professor Greb that she would borrow records from a local music store “just for the sake of advertising the records to these young operators with their little galena sets. And we would play up-to-date, young people’s records. They would run down the next day to be sure to buy the one they heard on the radio the night before.” And she encouraged regular listeners by running contests. “We would ask them to come in and sign their names, where they lived, and where they had their little receiving sets … and we would give away a prize each week.”

(This is the basis for KCBS’ claim to be the nation’s first broadcasting station. In order to be first, a station would have to be on the air earlier than any other, broadcasting on a regularly scheduled basis, and would have to be “broadcasting” in the truest sense of the word. Almost all radio communication up until then had been point-to-point transmissions, with a specific person designated as a receiver. Herrold and his wife and students were transmitting to whoever could receive them. In later years, Herrold himself would claim that he was the first person to use radio for the purpose of broadcasting.)

In time, Herrold tired of the raspy sound of his spark transmitter. He began experimenting with other methods of voice transmission, searching for a method that would be free of any spark noise. He experimented with many types of sparks and arcs, until he fell upon a new concept. Arc-type street lamps of the time had a curious habit of “singing” — they would occasionally emit a humming sound, created by oscillations of the arc. Herrold reasoned that if he could raise the frequency of the oscillations above the range of hearing, then he could modulate it and use it as a carrier for higher-quality sound transmission.

Herrold and his students began experimenting on Herrold’s “arc-phone.” Newby recalled that, to raise the frequency of the arc, they had to enclose it in a tube insulated in alcohol; they later used distilled water. He said:

This was able to quench the arc, which would make it vibrate or oscillate at a higher frequency … and that’s exactly what (Herrold) was able to do.

As soon as he developed a carrier wave that would be inaudible to the ear, then it became necessary to talk into it so that you could hear it. So he put a microphone into the circuit with it, and when you would talk the microphone would get hot and burn up — burn the granules or the carbon dust out of it in a hurry. It would get so hot you would drop it. In fact, it was very soon that we learned you would get a shock or get electrocuted if you did not do all of this experimenting in the ground circuit.

Herrold got around this problem by wiring four or five microphones together, and water-cooling them to hold the temperature down.

By 1912, Herrold had perfected and tested his arc-phone to the extent that it interested the National Wireless Telephone and Telegraph Company in his work. National was a manufacturer of arc-based telegraph transmitters, which it sold to the armed forces. He installed his arc-phone system for the U.S. Navy at Mare Island and Point Arguello.

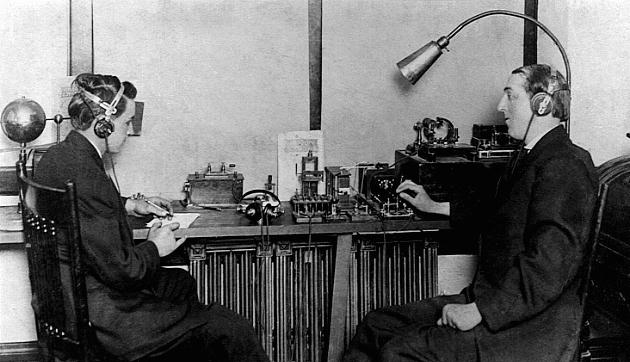

On June 20, 1912, he installed an arc-phone in the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco, and succeeded in contacting and talking with his San Jose station. With the stockholders of the company watching, and with two transmitters at each location to guard against breakdown, he set up communication with his student assistants in San Jose. This communication link was to continue on a regular basis for over eight months.

Herrold’s student assistants included Newby, Kenneth Sanders, Frank Schmidt and Emile Portal. Many of his students went on to play important roles in the establishment of wireless in this country. Some of them went into radio work during the war. Portal later operated an early broadcast station.

Up until this time, there was very little government regulation of wireless. Licenses were not issued, and Herrold’s station simply announced, “This is San Jose calling,” or, “This is the wireless telephone of the Garden City Bank Building of San Jose.” The Wireless Act of 1912 required licenses for the first time, and Herrold claimed his was the first to be issued for any voice transmission.

He applied for his license December 4, 1912. The new regulations required some form of call letter identification for all stations, although the station could choose its own, and Herrold chose “FN,” which was said to be backwards for “National Fone,” referring to the National Wireless Telephone and Telegraph Company. Subsequent experimental call letters assigned to Herrold were 6XE (portable) and 6XF. The Fairmont Hotel station was 6XG. Other call letters used in later years were SJN.

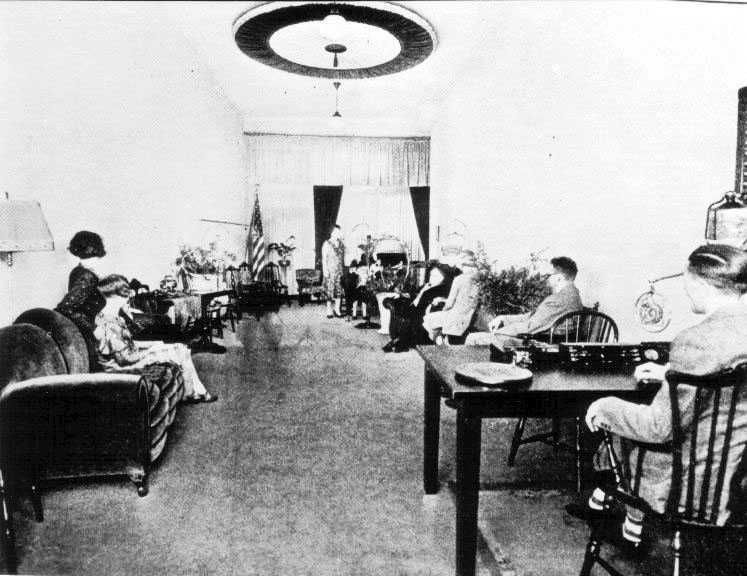

Herrold’s experimentation and expansion continued. He set up a listening room in the Wiley B. Allen Company, a San Jose music store, to help encourage interest in radio. Some two dozen telephone earpieces were connected to a receiver for the purpose of picking up Herrold’s broadcasts. In return, the company loaned records to Herrold for his music programs.

Herrold and his assistants conducted many tests of the station’s signal strength. A Model “T” pickup truck fitted with a receiver was used to test reception at various remote locations. A receiver was placed in a shack in the Santa Cruz Mountains, and a 500-foot antenna strung between two mountain peaks. Reception reports were received from a number of distant points, never failing to amaze. Herrold received a letter in 1933 from Leslie F. Sherwood, who had sailed regularly in and out of San Francisco in the years between 1911 and 1913, and received both Herrold stations quite frequently. He wrote:

The greatest distance I received good speech was abeam San Pedro. As to the quality, the signals were as clear-cut and smooth as the present day transmitters.

Newby himself received the signal as far as 900 miles distant on one occasion. On November 18, 1913, the Mare Island station was heard by a U.S. Navy wireless station in Bremerton, Washington (reporting that the record “Trail of the Lonesome Pine” came in extra good). The same day, a dispatch was received reporting reception by the Navy station at Arlington, Virginia, three thousand miles away!

1914 was an eventful year from Herrold. He ended his association with N.W.T.& T. early in the year, but continued to experiment from his school. On February 13, he was able to communicate with his arc-phone station at Point Arguello. This was, at the same time, the longest distance that two voice transmitters had ever communicated. Herrold was granted a patent for his arc-phone May 12. That year, the “San Jose Mercury-Herald” announced to the public that, at a specific time, a large blue spark would jump from Herrold’s Garden City antenna. It happened, exactly at the specified time. To this day, no one knows exactly how he did it.

About this time, Herrold’s station attempted its first remote broadcast. The event was a play being performed in the auditorium at Normal College (now California State University at San Jose). The carbon button microphones Herrold used had very limited pick-up range, and his students improvised a reflector to collect the sound out of an old wooden chopping bowl. The signal was transmitted to the bank building through an ordinary telephone connection. Newby related,

“We would use a phone, and they would take the receiver off of the hook and we would hold the receiver on the other end at the microphone of the transmitter. And it would go through; voices would go through pretty good.”

He told of another incident when they tried to broadcast a harp recital. They had to keep the microphone very close to the strings to pick up the harp with enough volume, and the mike upset the harpist so much that she couldn’t play a thing.

By 1915, San Francisco had completely rebuilt herself from the ruins of the 1906 earthquake, and she wanted to show off her new look to the rest of the nation. To celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal, the Panama Pacific International Exposition was held in the city, and elaborate buildings were constructed on vast grounds in what is now the Marina District. The Liberal Arts Building of the fair was to include a radio exhibit, and Dr. Lee DeForest was asked to set up a display.

In addition, Lt. Ellery Stone, who was San Francisco’s government radio inspector, visited Herrold in his San Jose laboratory, and arranged for him to make regular broadcasts to be picked up by a receiver at the fair. Herrold agreed, and broadcast six to eight hours of music daily for the duration of the Exposition, where its visitors could listen through headsets. These broadcasts proved the reliability of Herrold’s equipment. In addition, Dr. DeForest’s transmitter at one point refused to operate properly, and so his receiver was also tuned to the Herrold station to demonstrate the DeForest equipment.

Herrold’s broadcasting activities in San Jose continued until World War One. On July 31, 1918, however, all non-government radio stations were ordered shut down, to prevent any accidental dissemination of war information to foreign subversives. This ban was not lifted until the following year. During this time, Herrold continued the training of wireless operators at his school. When the ban was lifted, Herrold was back on the air with his arc-phone.

During the next two years, the station operated under a number of different licenses of different power and wavelength specifications. One was variable from 150 to 25,000 meters, and another was variable up to 1,000 watts in power.

Everything suddenly fell apart for Herrold in 1921. Broadcasting was now an activity being practiced by a number of radio stations around the country, including pioneer stations KDKA, WHA and WWJ. The government finally decided to regulate this new kind of radio transmission. It decreed that all stations were to have a new type of license, known as “limited commercial,” and all stations were to share time on a single frequency, 360 meters. This announcement was fatal to Herrold and to his arc-phone. He explained in a letter, dated 1932:

The Herrold system of radio telephony would not work on wavelengths under 600, and the allocation of 360 meters by the government was fatal. Over two decades of work, and expenditures of over $80,000 and a lot of patents went on the scrap pile.

Herrold received a new broadcast license December 9, 1921. The call letters assigned were KQW. Despite the losses he had suffered because of the new regulations, he continued with his work, constructing a tube-type transmitter. He was still an innovator, however. While most stations of that era got the DC current required to operate the transmitters from batteries charged by motor generators, Herrold tapped directly into the city’s streetcar power lines. He constructed a vertical cage antenna, also a first, and was back on the air as KQW.

During the KQW era of Herrold’s school, the station would announce, “This is Herrold Laboratories, broadcasting over our ‘bulb-phone’.” Herrold referred to tubes as “bulbs,” as it was natural for his arc-phone to become a “bulb-phone.”

Another innovation of Herrold’s during these years was used in the broadcasts of the Elks’ Club Band, a regular program on KQW. Instead of using a single microphone to pick up the band, Herrold’s crew attached a carbon button microphone to each instrument, anticipating today’s recording methods by almost forty years.

DOC HERROLD SELLS KQW

KQW operated for several years under Herrold’s direction. But, although Herrold was an electronics genius, he found himself unable to efficiently handle the school’s finances. Complicated by the losses incurred in the collapse of his arc-phone, in early 1925 Herrold found himself forced to put the station up for sale.

About the same time, the Rev. Dr. William Keeny Tower, pastor of The First Baptist Church in San Jose, became interested in the idea of a radio station operated by the church. His plan was approved by the church board, and Dr. Towner contracted with Harry Saine, a personal friend and electrical engineer, to help obtain a license and build the station. But a radio license was not as easily obtained as had been hoped, as Saine later wrote to a friend:

We learned that Dr. Herrold had a license, but did not know that he wanted to dispose of it. We tried to contact Dr. Herrold but for some reason or another we were unable to do so for some three or four weeks. At last I got an audience with him, only to learn that he had given a thirty day option to another group only a few days before, and had turned over to them his old license. Things looked bad, for we knew that the government would not grant two licenses for this community.

Dr. Herrold was very favorable to The First Baptist Church, but his hands were tied. The group who had obtained the option was a civic organization, and did not desire to use the license themselves, but wanted to see that something substantial and definite was done to the end that San Jose would have a radio station of which it would be proud.

There followed three weeks of negotiations — three weeks in which meeting after meeting was held and in which I was trying to show them that The First Baptist Church was the one that should be given this opportunity. There were others after this license, but I believe the Lord was on our side, for the day before their option was to expire it was turned over to us.

In as much as the acceptance had to be made in person, we immediately got in touch with Dr. Herrold and he signed it over to The First Baptist Church. In May, 1925, Dr. Towner, Frank Curtis, and I went to San Francisco and got the consent of Colonel Dillon (the Radio Inspector for the District) that The First Baptist Church could take over Dr. Herrold’s license to operate with a power of 500 watts on 231 meters.

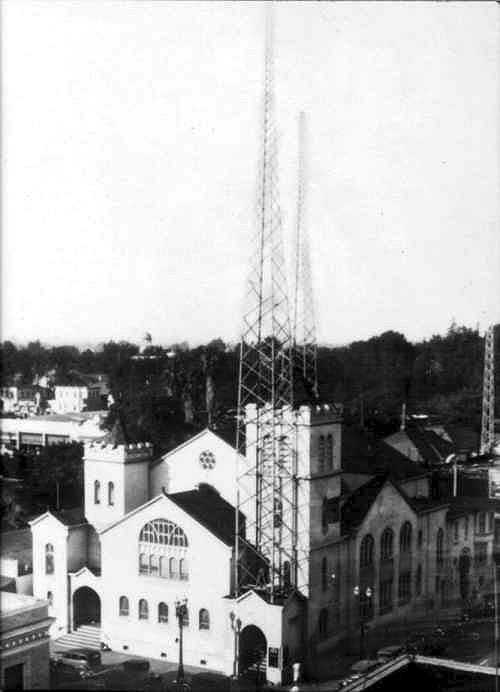

The license was ours but a big job was ahead — that of raising $20,000 with which to put the station in — so a general meeting of the church was called for that purpose. Frank Isenberger had charge and he caused to be erected on the pulpit two towers to represent the radio towers, with ribbons from one tower to the other as the aerial. Then pledges were called for and, as they were given, the totals were added at regular intervals and placed on one of the towers — beginning at the bottom and going up towards the top. When that meeting adjourned, the top figure on the tower showed more than $20,000 in pledges.

With the money pledged, we could then go ahead and contract for the equipment. This was done by purchasing a new Western Electric 500 watt transmitter. The towers were furnished and erected by the Pacific Coast Steel Company. The excavation for the bases and the setting of the steel stubs in cement was supervised by Guy Lunty — each base containing approximately sixteen tons of cement. The front entrance of the church was torn away and, after the front tower was erected, the front was rebuilt around it.

Two legs of the back tower went up through the church and the other two set in a strip of land in back of the church and owned by the church. These towers were 150 feet high and had a steel flag pole 10 feet long on top of each tower, making the top of the flag poles 160 feet above ground.

On Saturday night at 7:30 PM, December 5, 1925, the station went on the air on a wavelength of 231 meters (later moving to 1010 kc.). On January 15, 1926, Fred J. Hart took over control and operation of KQW.

Doc Herrold stayed on with KQW as a technician for a few years, but soon dropped out of the operation entirely. He tried his hand at selling radio receivers for a while, and later hosted children’s’ programs on KTAB and KFWM, both in Oakland. However, he never again regained a position of importance in broadcasting. Herrold, the man who watched the business of radio broadcasting grow up around him and leave him behind in the dust, died unrecognized in a Hayward rest home on July 1, 1948, at the age of 72.

KQW’S POST-HERROLD YEARS

Just over a year after Dr. Charles Herrold sold his San Jose radio station, KQW, to the First Baptist Church, it was sold again. Fred J. Hart, who had been managing the station for the church, purchased the license and facilities on January 15, 1926.

Hart, who had been a farmer for many years, was now operating the station as a service to Central California farmers, apparently the first station in the area to whole-heartedly do so. “If you had a problem,” he later recalled, “you wrote us and whatever it was, we’d get the answer for you.” He was assisted in this endeavor by Stanford University, the University of California and the Agricultural Extension Service. In four years, KQW handled no less than 25,000 questions.

Cooperating with government agricultural agencies, KQW set up a system of nine shortwave radio transmitters that helped gather market news and price information. This, according to Hart, was “so the farmer could known the prices as soon as the buyer.”

KQW was also the first area station to begin full-fledged efforts in advertising, and the station soon had a host of sponsors. They included the Union Oil Company, the Southern Pacific Railroad and the Sperry Flour Company. Hart’s system of advertising was 25 years ahead of its time: instead of selling entire programs to sponsors, he sold them what are now called “spot announcements” — short commercials read during the beginning, middle and end of each program. Hart said this insured the “political independence” of the station’s programming. The only exception was Sperry Flour, which purchased an entire cooking show.

Another unique arrangement was the one made with Union Oil. That company paid the bill for telephone lines to a remote studio located in the Agriculture Building at the State Capitol in Sacramento. “Union Oil was our biggest advertiser,” said Hart. “They paid us to maintain the lines to Sacramento, and all we had to do in exchange was announce each time we used them, ‘These lines are maintained for the benefit of rural California by the Union Oil Company’.”

On January 14, 1930, Hart was given an option to purchase the station from The First Baptist Church. A bill of sale was signed on March 31 of that year, with the license being transferred to the Pacific Agricultural Foundation, Ltd. The church was paid a specific sum of money, the payment of which was spread over a number of years. In addition, the church received the right to broadcast religious services up to five hours each Sunday without cost.

In 1934, Hart sold KQW and the Pacific Agricultural Foundation to Ralph Brunton and Charles L. McCarthy. Brunton was one of the owners of KJBS in San Francisco, and McCarthy was the Manager of Station Relations for NBC in San Francisco. Hart continued to manage the station as President of the foundation, so that the station continued its service for many years afterward.

KQW’s studios were moved to the KJBS building on Pine Street in San Francisco, where both stations operated under one roof for several years. An auxiliary studio continued to be maintained in San Jose. The power of the station was increased, first to 1,000 watts, and finally to 5,000 watts in 1935.

KQW became the San Jose affiliate of the new Mutual-Don Lee Network in 1937, but lost its network connection in 1941. Without quality network programs, it was unable to make a major impact in the local radio market.

But the fate of the station changed in 1942. That year, CBS offered to purchase KSFO, its San Francisco affiliate, but the offer was rejected by KSFO’s owners. Immediately thereafter, CBS approached KQW with an offer of affiliation, which was accepted. KSFO had occupied a lavish studio complex in the Palace Hotel, which was owned by CBS; KSFO was evicted, and KQW moved in. Charles L. McCarthy was named the General Manager of KQW, and also became the regional Vice President for CBS.

After the affiliation with CBS, the KQW programming spotlight shifted from agricultural to network programs, although regular farm features continued to be an important aspect of the station’s schedule. The auxiliary studios in San Jose were completely abandoned, and all operations shifted to the Palace Hotel. CBS wanted a San Francisco affiliate, but the city of license was still officially San Jose. As a result, an announcer was always on duty at the transmitter, whose sole duty was to make the station identification announcement between each program, just to keep everything legal in the eyes of the F. C. C. KQW continued to operate in this manner throughout the forties.

As America entered the Second World War, CBS quickly became a leader in war coverage, with some of the nation’s brightest young radio journalists filing daily reports from the front. The voices of Edward R. Murrow, Walter Cronkite, John C. Daly and Eric Sevareid were heard daily with their reports from Europe.

San Francisco’s location on the Pacific made it the logical choice for CBS to center its news-collecting efforts for the war in the Pacific. The network operated a large news-gathering complex in the KQW studios at the Palace Hotel. A crew of field reporters followed the troops in the Pacific with wire recorders and short wave transmitting equipment. Their reports were received at KQW and relayed Eastward to a waiting public.

A regular CBS program called “Dateline San Francisco” was one of the more important news programs that originated from that city during the war. The entire KQW news staff joined forces to produce this program, a lively report on the feature side of the news in the war and the West.

After the war, KQW found itself in a competition with KSFO for the use of its frequency of 740 kc., the last 50,000 watt frequency available in Northern California at that time. The competition was a long and protracted one.

In 1941, when KSFO was still the CBS affiliate in the area, the network had entered into an agreement with KQW which called for KSFO to take over KQW’s frequency and increase its power to 50,000 watts. KQW, which was by then operating at 5,000 watts on the frequency, was to move to KSFO’s dial position.

The entire transaction was awaiting approval by the F.C.C. when a wartime freeze was placed on all station changes. By the end of the war, however, the CBS affiliation belonged to KQW, and CBS was not about to give up its plans for a 50,000 watt affiliate in the Bay Area. It filed a competing application for a power increase at 740.

After lengthy hearings, the F.C.C. granted the power increase to the original applicant, KSFO. However, the management of KSFO began to have doubts about the future of AM radio, and were putting all of their money into their new television station, KPIX (Channel 5). Negotiations were re-opened with CBS, and the result was that KSFO gave up its claim for the 740 dial position, in exchange for the CBS-TV network affiliation for San Francisco.

In 1949, CBS purchased the license of KQW outright, and changed the call letters to KCBS. An elaborate multi-tower antenna site was constructed at Novato in Marin County. The new high-power network-owned facility went on the air in 1951.

KCBS programming during the 1950s consisted of a mixture of network programs and disk jockey music programs. In the late fifties, KCBS developed a concept they called “Foreground Radio.” Under the leadership of Jules Dundes and Maurie Webster, a sort of hybrid of personality, news, and the area’s first telephone talk show was developed. Owen Spann ran the morning commuter’s disk jockey program at the station, but several talk shows — particularly “Viewpoint” and “News Conference” — were integral parts of the KCBS format.

This emphasis on information programming resulted in KCBS abandoning all music programs in 1968 and beginning round-the-clock all-news programming. KCBS became the first station in the Bay Area to successfully utilize this concept. KCBS has continued its all-news format with little competition for the next thirty years.

RELATED EXHIBITS:

![]()

REFERENCES:

“A History of Santa Clara County,” by Eugene T. Sawyer. The Historical Record Co., Los Angeles, 1922.

“The Journal of Broadcasting,” February 15, 1959: “The Golden Anniversary of Broadcasting,” by Prof. Gordon B. Greb.

Transcript of interview between Prof. Gordon B. Greb and Ray Newby, Stockton, California, January 9, 1959. Unpublished; from KCBS historical files.

“Chronological History of KCBS (KQW).” Unpublished; from KCBS historical files.

Copy of patent number 1,096,717. From KCBS historical files.

Handwritten article “A Brief History of Radio Station KQW, San Jose, California, the Pioneer Broadcasting Station of the World” by Harry Saine, and directed to Ray Grisham of Kelsey, El Dorado County, California. Supplied to the author by Cecil Lynch.

Interview between author and Armon Humburg, a former acquaintance of Herrold. San Francisco, California, October 9, 1970.

“First Quarter Century of American Broadcasting,” by E. P. J. Schurick. Midland Publishing Company, Kansas City, 1946.

Interview with Gordon R. Greb, KCBS program “News Conference,” broadcast April 23, 1962.

The Federal Radio Commission Station List, as authorized on 11/11/1928. With research by Barry Mishkind, 1993-94.

Copyright © 1996-2022 John F. Schneider. All rights reserved.

What’s missing is information on what year the KQW transmitter was moved from the church property to Alviso. That’s where the 5kW transmitter was located. I recall a man named Carroll Reimers who owned United Radio & TV in San Jose (1960’s & 1970’s) telling me about his years as an engineer at KQW. Carroll told me the station was 5kW day and 1kW night and that the directionality of the night signal was very severe. I was just a teenage kid at the time and I didn’t know enough to ask him more detailed questions about the xmtr site. I didn’t even realize that 1010 was the KQW frequency and not 740. Incidentally, the 1010 frequency was ‘quiet’ for a number of years until Grant Wrathall, Sr. received a CP to build a daytime facility at 1010 for San Francisco in 1957. KSJO San Jose (on 1590) had also applied for the 1010 facility for San Jose, contending in their application that the allocation belonged not to SF, but rightfully to SJ. KSJO (now KLIV) contended that the 1010 facility could be better used in SJ because it could be 24/7 facility whereas in SF, it could only be a daytimer. The commission was not convinced and they gave the CP to Wrathall.

GREAT information, Mark! Thank you for sharing this info, and the info below.

DJ

I was able to find the FCC history cards on KQW/KCBS and they are very interesting (and voluminous) – so I’ll cut to the chase. The first application to move the xmtr site out of downtown San Jose was made in 1930 to a site “..7 to 9 miles NW of San Jose, Cal…” This would likely be Alviso (an unincorporated hamlet at the bottom of SF Bay). However, the Pacific Agricultural Foundation also had applications to move to SF, Sacto and Fresno. FInally in 1939, KQW was granted a CP to move the xmtr to Alviso with a daytime power of 5kW and a nighttime power of 1kW. In July 1940, a CP was granted to increase day and night power to 5kW. It also looks like KQW applied to move frequency to 740 sometime later in 1941. So the station did operate on 740 from the Alviso xmtr site and did so until 1951 when the Novato site came online at 50kW day and night. My uncle used to hunt for duck out in Alviso and I remember him telling me there were radio towers there when he hunted there as a young man. I don’t know when the towers were removed (probably sometime after the move to Novato was complete). Some 30 years later, CBS as the licensee of 1550 AM actually applied for and received a CP to build a 50kW facility for 1550 in Alviso! However there was community opposition to the idea of 4 radio towers going up in their town and it was also discovered that a 50kW AM station in San Jose did not have the same market value as a 10kW/5kW facility licensed to SF. That realization along with community opposition killed the 1550 move to the South Bay

Does anyone know if any of the KZQ broadcasts from the 1930’s were somehow recorded? Specifically… Aug 23, 1937?

I’m not familiar with KZQ. Was that a Bay Area radio station, Mark?

DJ

I am not familiar with that station. Mark

[…] Charles Herrold, also known as “Doc,” invented and pioneered a radio station in San Jose, California, which went under many callsigns before settling on KQW. These included FN, 6XF, SJN, and 6XE. […]

Hello Mark, this is wonderful information. Were you able to determine the name of the play that Herrold broadcast from Normal College?

Barry,

Mark didn’t mention anything about Normal College in his comment. (In fact, neither of the Marks mentioned it in their comments.)

Hello John,

I meant to address my previous comment to you. I am researching the history of audio drama and was referencing the following from your article:

About this time, Herrold’s station attempted its first remote broadcast. The event was a play being performed in the auditorium at Normal College (now California State University at San Jose).

Do you know the title of the play that was performed? If not, what source did you get this information from? I’d like access it in hope of including the title of the play in a piece that I am writing.

Best regards,

Barry

Barry,

I’m guessing that the “John” you’re referring to is John Schneider, who is the author of this article. You may contact him directly through his amazing and wonderful website, “The Radio Historian.”

DJ

[…] Area. The first entertainment broadcasts in the United States came out of San Jose in 1912, when Charles “Doc” Herrold started broadcasting musical concerts by dangling a microphone in front of a wind-up gramophone. […]

[…] Area. The first entertainment broadcasts in the United States came out of San Jose in 1912, when Charles “Doc” Herrold started broadcasting musical concerts by dangling a microphone in front of a wind-up gramophone. […]

[…] Area. The first entertainment broadcasts in the United States came out of San Jose in 1912, when Charles “Doc” Herrold started broadcasting musical concerts by dangling a microphone in front of a wind-up gramophone. […]

[…] Area. The first entertainment broadcasts in the United States came out of San Jose in 1912, when Charles “Doc” Herrold started broadcasting musical concerts by dangling a microphone in front of a wind-up gramophone. […]

[…] in 1934 when he joined with Ralph Brunton, one of the owners of KJBS, and together they purchased KQW in San […]